By Jennifer Bentzel and Emily Esworthy/IMA World Health

N

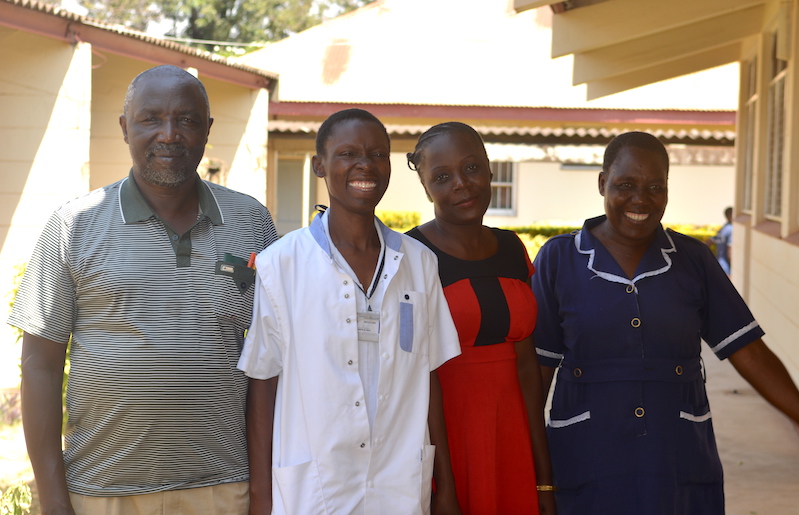

urse Joy Agutu enjoys her work. She, along with a doctor and a few other nurses, conducts cervical cancer screening and treatment for women at Shirati KMT Hospital in Tanzania’s Lake region. Agutu is a true champion for cervical cancer screening, encouraging and counseling women wherever she goes and getting periodic screenings herself. She also enjoys working with elders and community leaders, whom she describes as “cooperative and encouraging,” to promote village screening campaigns. Her days are rewarding.

Indeed, reducing cervical cancer deaths in Tanzania should be easy and rewarding; health workers know screenings are important, and the supplies cost only a few cents per patient. Plus, demand is high. The screening campaigns IMA World Health has conducted in Tanzania’s Mara and Lake regions have frequently shattered expectations, with lines of women snaking through the neighborhood as they wait their turn.

Yet year after year cervical cancer continues to kill more women in Tanzania than any other type of cancer.

For more than six years, IMA World Health—with funding from the IZUMI Foundation, American Baptist Churches (USA), Week of Compassion, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and private donors—has supported Shirati and other health facilities to ease the burden of cervical cancer by training health workers, providing testing and treatment supplies and equipment and creating referral linkages to larger hospitals for those who require additional treatment. Through this support, 24,000 women have been screened to date—most of whom would otherwise have no access to these services.

But the challenges are many, and few have a better understanding of them and their solutions than Agutu and the team at Shirati. Recently, they sat down with IMA staff to highlight the challenges and discuss how, together, we can strengthen the response to the rising number of cervical cancer diagnoses and deaths.

BARRIERS TO CERVICAL CANCER TREATMENT

Challenge: Lack of supplies

The basic supplies for cervical cancer screenings are fairly inexpensive and easy to obtain: gloves, speculum, vinegar, cotton swab, flashlight. But considering the volume of need, these supplies vanish quickly. Shirati relies on donations from IMA World Health and our partners to maintain their stock of screening supplies. These are in such demand that the health workers who conduct the screenings, like Nurse Agutu, work as volunteers so that all funds can go to supplies and outreach.

In a country where urgent needs compete for limited health care resources, cervical cancer screening supplies—and indeed the screenings themselves—are not a given or, in most cases, even a priority. Since many of the women who are most in need of screening are often those who suffer the hardest from poverty, screenings through Shirati’s outreach campaigns are free. There is no revenue to self-fund the program and replenish supplies—meaning hundreds if not thousands of at-risk women are unable to receive screening when supplies run out.

Challenge: Lack of follow-up

Shirati staff estimate that about one third of the women they have screened recently have signs of cervical cancer. Patients with larger or suspicious lesions require referrals for treatment at a larger facility. Women who present large or suspicious lesions require a referral to a larger hospital for more advanced treatment; Shirati staff estimate 1 in every 4 women screened need further testing.

The trouble is the closest referral hospital is Bugando Medical Center, which is nearly 300 kilometers away—a minimum five-hour trip by car. In addition to the distance and cost of bus fare, the cost of treatment at Bugando is a prohibitive factor. As a result, Shirati staff say only about 2 percent of women with the most troubling signs of cervical cancer get the follow-up treatment they need.

Additionally, women whose screenings show early stage symptoms can receive cryotherapy treatment the same day at Shirati for free, but many refuse because they have to abstain from sex for a month after treatment.

Challenge: Education

Many women know someone who has died of cervical cancer, which often prompts their desire to be screened. Still, the full scope of prevention and treatment is not well understood. This lack of understanding is another reason some women neglect to follow through on referrals or refuse treatment altogether. Nurse Moureen Mbise, the Nursing Officer in Charge at Shirati, says many of their patients mistakenly believe they are not in danger unless they have noticeable symptoms. By then, it’s often too late. But educating the public requires staff time, transportation and materials—all resources the hospital doesn’t have.

OFFERING SOLUTIONS TO THE CHALLENGES

Limited resources and competing priorities have made cervical cancer a low priority across both national and local levels of the health system in Tanzania. While they continually go the extra mile for their patients, the team at Shirati know there is so much more they could do if they had more resources.

In addition to purchasing more screening supplies, they would seek additional training for themselves and their colleagues.

More funding would also help with patient follow-up: the staff could buy phone credits to contact patients, train community health workers to follow up with patients, pay for biopsies, and cover transportation costs to take women with more advanced cancer to Bugando.

The team says they would provide materials to religious leaders, such as sermon guides, posters and pamphlets, to increase community awareness. They would incentivize these influential leaders to educate community members about the importance of screenings and follow-up treatment.

They would purchase a LEEP machine, along with the requisite training, that would allow them to treat both small and large lesions onsite.

This wish list is basic, but these health workers know it will save lives. IMA World Health has seen the impact of a well-supported cervical cancer screening and treatment program, and we are committed to supporting Shirati KMT Hospital and other hospitals to address the challenges that make cervical cancer so deadly in Tanzania.